The Most Beautiful Program Ever Written

A Lisp interpreter written in Lisp

It’s my 5th time trying to follow this video and things finally start to click in my head. So I think if I write down what is talked in the video, then I can just read my blog post for another 15 times instead of going through the video, that would be convenient.

OK, here is a gist of it. This guy is writing an Scheme interpreter in Scheme.

Let’s start from setting up the environment first so we can type along afterwards.

Environment Setup

The programming language used in this talk is a dialect of Scheme Chez Scheme, you can download and install it from here.

There is a pattern matching library used in the talk pmatch, you can find the source code from here.

Scheme Basics

The talk begins with a brief introduction to the Scheme language.

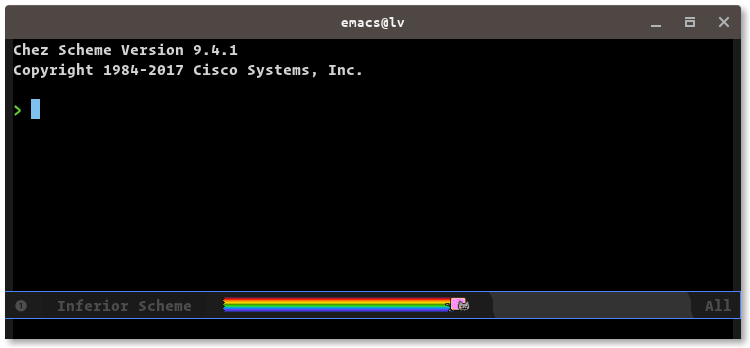

The REPL

If you have never worked with Lisp, REPL stands for Read Eval Print and Loop, it is an interactive programming environment that allows you to execute the program as you type it in. Now we fire up the REPL by just type scheme in the terminal. Or if you are using Emacs as I am, you can just M-x run-scheme.

List and Symbol

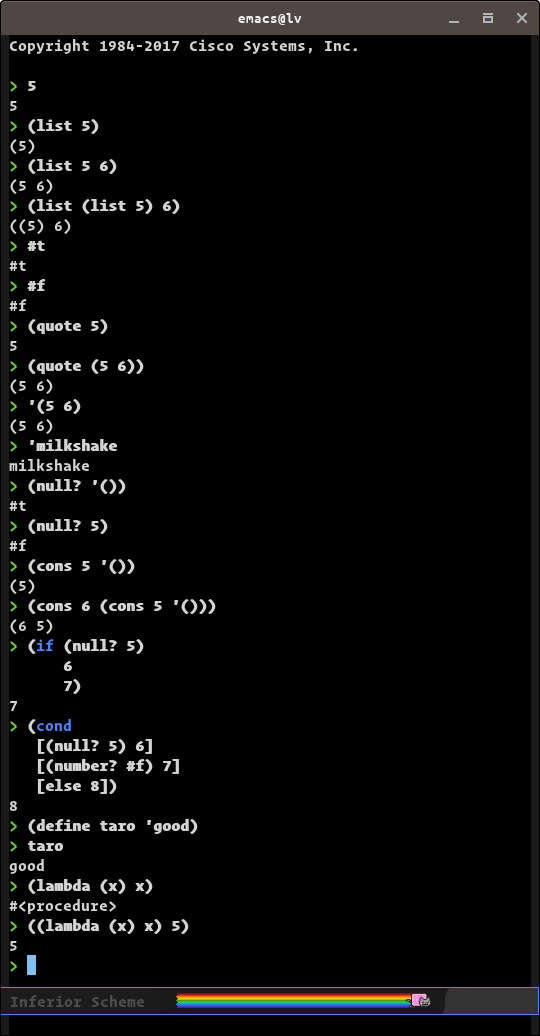

Lisp is all about list processing, let’s look at some simple programs.

Let’s explain them a bit.

First, 5 will evaluate to 5, that’s simple.

A list can be created by using (list ...), it can also be nested.

#t stands for true and #f stands for false.

quote anything will give you back a symbol of that thing. Symbol is kind of like a variable in other language, it might be bound to some value or it might not.

' is a short hand for quote.

null? is a function, it returns true if its arg is null or false otherwise.

cons will attach a value to the beginning of a list.

if is like if in other languages.

cond is like switch in other languages.

define is like assigning to a variable.

lambda is a way to define functions, e.g. (lambda (x) x) means that this is a function that returns what it takes in. In other words, it is the identity function.

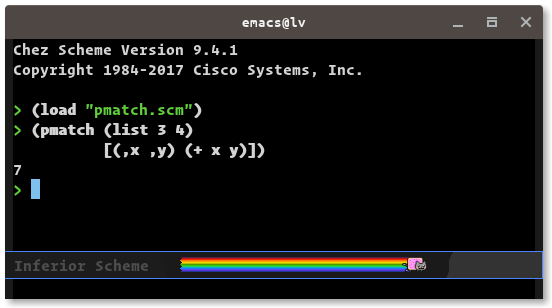

Pattern Matching

How to use pmatch is best explained through an example.

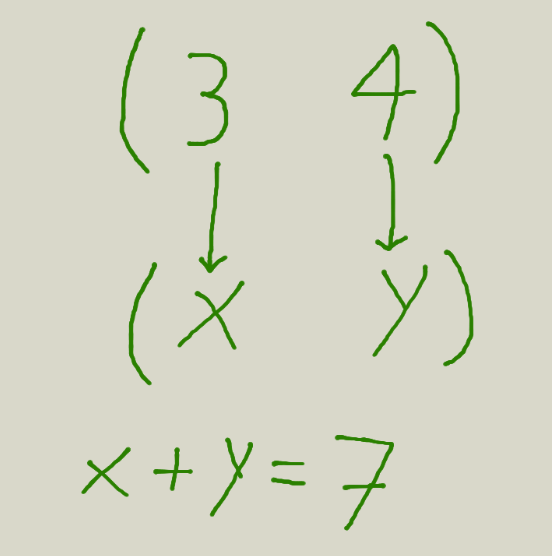

Which is basically doing:

OK, now we know everything to write a interpreter!

Write an interpreter

What do we want to first interpret? How about a number like 5?

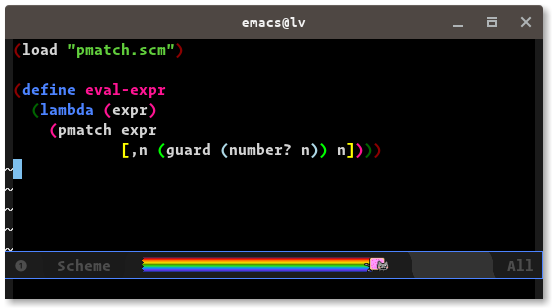

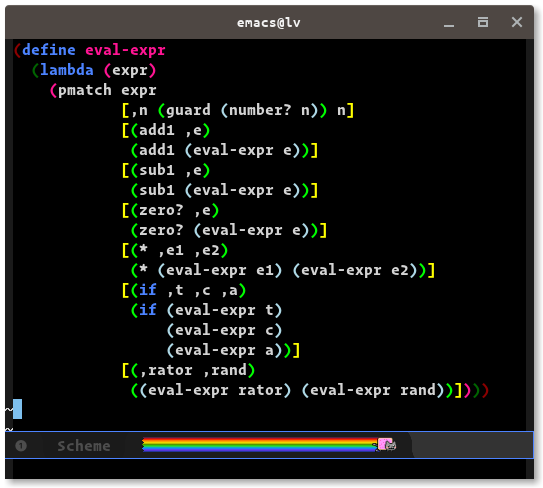

The interpreter that will interpret only numbers can be written as follows:

As we can see, it is trying to pattern match the given expression to ´n´ where n is number, and if it finds a match, it return n itself.

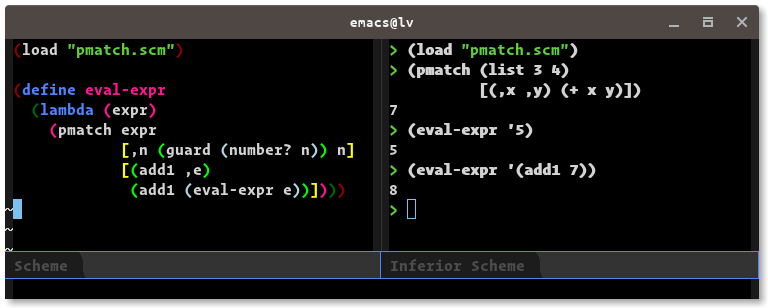

What do we want to interpret next? How about add1?

add1 is a function in scheme that adds 1 to its argument.

You can see that we use the add1 in Scheme to implement the add1 in our language. Pay attention that recursive eval-expr there, so that we can handle nested expressions like (add1 (add1 6)).

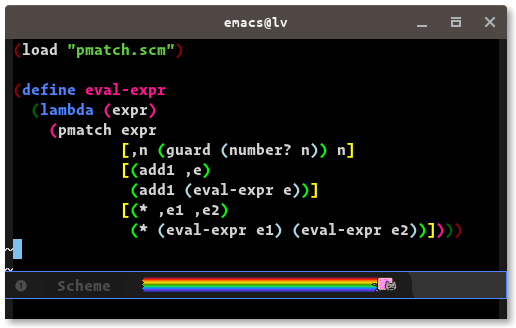

Next we will do multiplication.

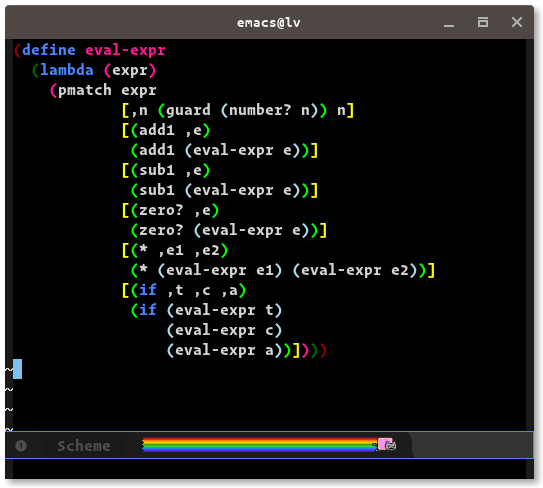

OK, let’s add some more.

OK, now the boring part has ended. Let’s begin the fun part.

The core of this interpreter consists of the following 3 parts.

Application, lambda and variable lookup

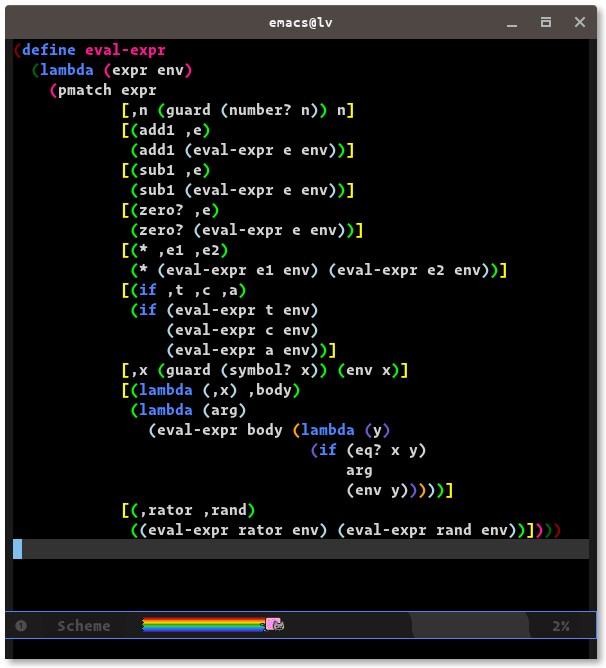

Let’s now add application.

,rator stands for operator and ,rand stands for operand. This is rather straightforward, we first eval the operator expression and then eval the operand expression and apply the former to the latter.

Now let’s try to add lambda expression. This is the most difficult part so don’t expect to understand it in one go. And even you think you understand it, you probably don’t.

Let me present it to you first, then we can explain it.

This is the final version, now let’s explain everything.

I find it’s more important to understand what is happening on a higher level, that will make reading the code much easier.

So we are trying to interpret lambda expression, but what is the outcome? Yes, a procedure that we can call later, to be precise a Scheme procedure. So how do we create a Scheme procedure? You guessed it, lambda! So, the lambda in our language will be interpreted to the lambda in Scheme.

Let’s take an example, say we want to interpret the expression (lambda (x) (* x 2)), what is x? It doesn’t really mean anything alone but an indicator that will be used in combination with the body (* x 2). Then what is the value of x? We don’t know yet, as said it is just an indicator, a symbol, there is no value assigned to it yet. But when the value will be known? When we are calling it of course.

So based on what we now know, lambda expression can be interpreted as a Scheme procedure like this:

(lambda (arg)

(eval-expr body))What is arg here? It will be the argument with which this lambda will get called. There is a problem here. When we eval the body, which in this case looks like (eval-expr '(* x 2)), how do we connect the arg 5 to x? In other words, at run time when the Scheme lambda gets called with 5? how do the interpreter know that now the x should be evaluated to 5? The answer is to introduce a environment env. env is a procedure that takes one argument. So when we trying to look up a symbol in the environment, we just call it with the symbol: (env x).

So now back to the problem, when evaluate the body we just need to provide the right environment, so that when we look up x later, it will yield 5, which is the arg.

Now with all these knowledge, you can read the code and see if you can understand it better.

Verify everything works

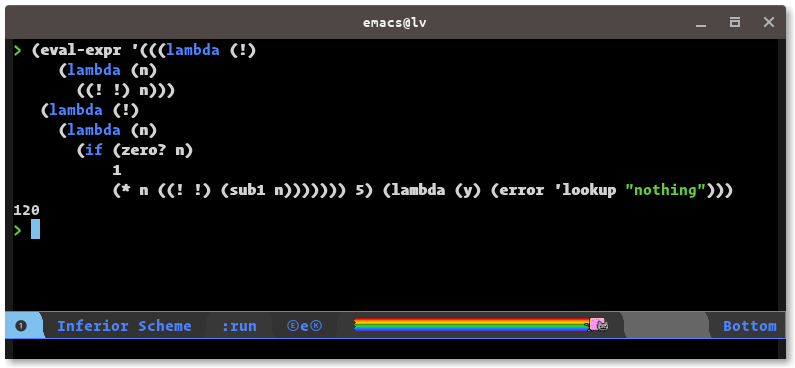

We will test our interpreter with a program that calculates factorial numbers.

(define factorial

((lambda (!)

(lambda (n)

((! !) n)))

(lambda (!)

(lambda (n)

(if (zero? n)

1

(* n ((! !) (sub1 n))))))))And tada, it all works!

Congratulations, now you understand the most beautiful program ever written!

Well, if not, then just go back and re-read this blog post or re-watch the video until everything becomes clear.

Warning, you may wake up during night or miss bus stop if you keep thinking about all the nested lambdas. Other than that, you will be fine.

Share this post

Twitter

Google+

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Email