SICP Goodness - Why you don't need looping constructs

About different types of recursion

Do you think Computer Science equals building websites and mobile apps?

Are you feeling that you are doing repetitive and not so intelligent work?

Are you feeling a bit sick about reading manuals and copy-pasting code and keep poking around until it works all day long?

Do you want to understand the soul of Computer Science?

If yes, read SICP!!!

I was quite shocked when I first read the following text from the book:

… As a consequence, these languages(Ada, Pascal and C) can describe iterative processes only by resorting to special-purpose “looping constructs”, such as do, repeat, until, for, and while. The implementation of Scheme … does not share this defect. …

This basically says that looping structures are NOT necessary.

WHAT!!??

I know, take a deep breath, everything will be fine.

In order to understand why, we must understand recursion.

Recursive Procedure

The first concept is recursive procedure. This is very easy to understand, if a procedure is defined in terms of itself, then we can call this procedure recursive procedure.

Let’s give the example in the book.

Here we define a factorial function.

(define (factorial n)

(if (= 1 n)

1

(* n (factorial (- n 1)))))This is a direct translation from the definition of factorial in math. Because the procedure is defined in terms of itself, it is called a recursive procedure.

Linear Recursive Process

Now let’s analyze the execution of this factorial procedure process.

(factorial 5)

(* 5 (factorial 4))

(* 5 (* 4 (factorial 3)))

(* 5 (* 4 (* 3 (factorial 2))))

(* 5 (* 4 (* 3 (* 2 (factorial 1)))))

(* 5 (* 4 (* 3 (* 2 1))))

(* 5 (* 4 (* 3 2)))

(* 5 (* 4 6))

(* 5 24)

120We see a pattern here, the shape of the execution process first expand and then shrink. Since the amount of information needed to keep in memory grows linear with n, we call this type of process linear recursive process.

Linear Iterative Process

Now let’s take a different perspective on computing factorials. We can describe the computation by saying that the counter and the product simultaneously change from one step to the next according to the rule:

product <- counter * product

counter <- counter + 1

Translate this into code we get:

(define (factorial n)

(fact-iter 1 1 n))

(define (fact-iter product counter max-count)

(if (> counter max-count)

product

(fact-iter (* counter product)

(+ counter 1)

max-count)))Let’s again try to examine the shape of this process:

(factorial 6)

(fact-iter 1 1 6)

(fact-iter 1 2 6)

(fact-iter 2 3 6)

(fact-iter 6 4 6)

(fact-iter 24 5 6)

(fact-iter 120 6 6)

(fact-iter 720 7 6)

720The shape here looks very different from the previous process.

This time, every execution step returns a new self with all the values needed for the next step. Whereas in the previous process, each step does not return but put more work into memory.

We can see that here the number of steps required grows linearly with n, such a process is called a linear iterative process.

In short, the execution of a recursive procedure can be a linear recursive process or a linear iterative process (or something else like tree recursive process).

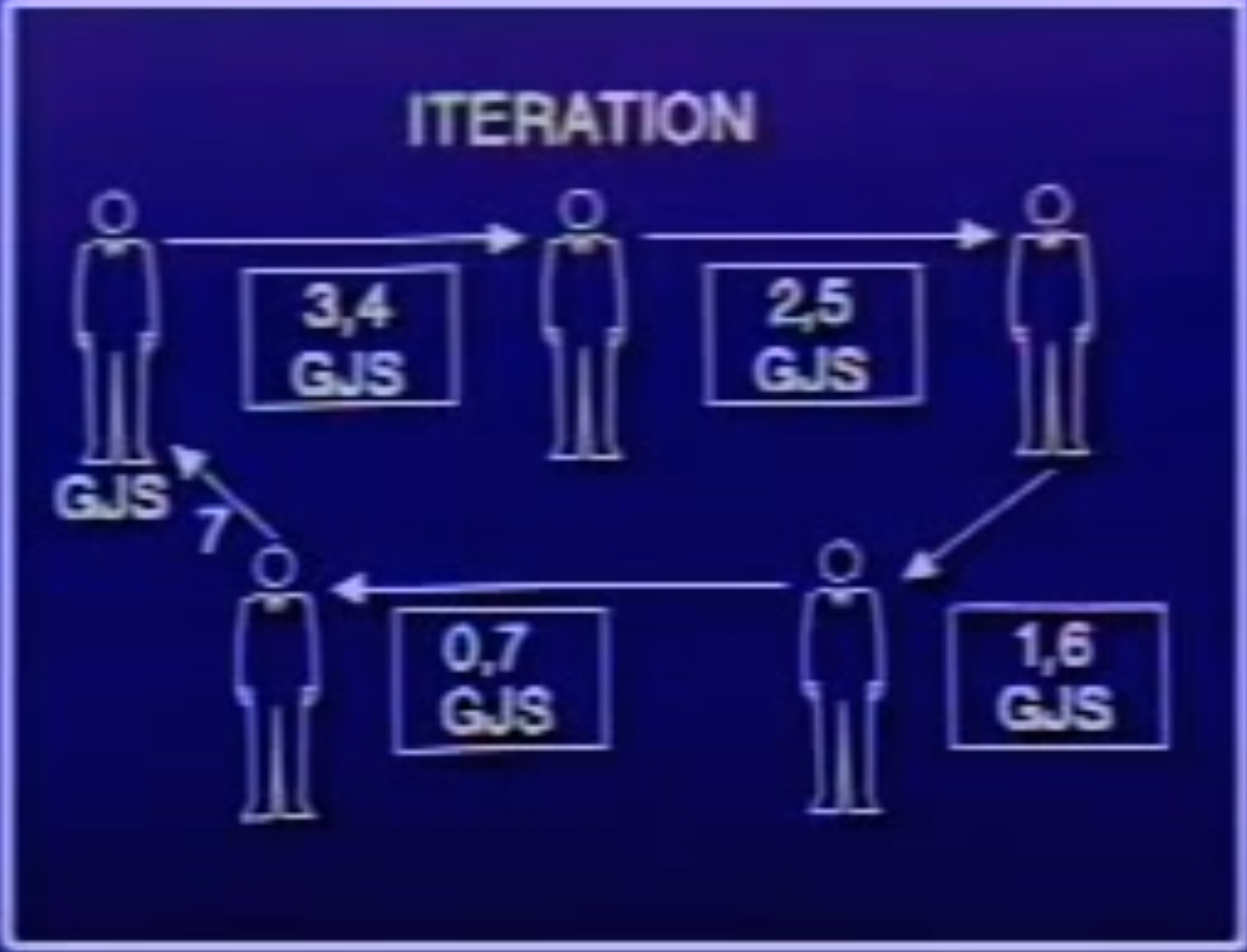

Iterative V.S recursive process illustrated

Sometimes the key to deep understanding is to see more examples. So now let’s examine another similar example. This time is to calculate the sum of two numbers.

The iterative process:

(define (sum a b)

(if (= a 0)

b

(sum (- a 1) (+ b 1))))

Let’s use this screenshot to explain how the process looks like. The author of the book GJS wants to calculate the sum of 3 and 4 using the above sum procedure. But he is too lazy to do the work, so he deligates the work to someone else. He writes the numbers 3 and 4 and his name GJS on a paper note (He writes his name to let people know who to report to if he gets the final anwser). Now he passes the note to the next person A. A is also lazy, he does a minus 1 and b plus 1 and change the numbers on the paper to be 2 and 5 and passes it to the next person B. Well B changes the number to 1 and 6 and passes to C. C changes the numbers to 0 and 7 and passes to D. Finally D knows the anwser (because now a is 0), and return the answer 7 to GJS.

Note two things here.

- Ther is only one note through the whole process.

- Once the person finishes his work, he can pass the note to next person (or give the final answer) and go home. There is no need to stick around.

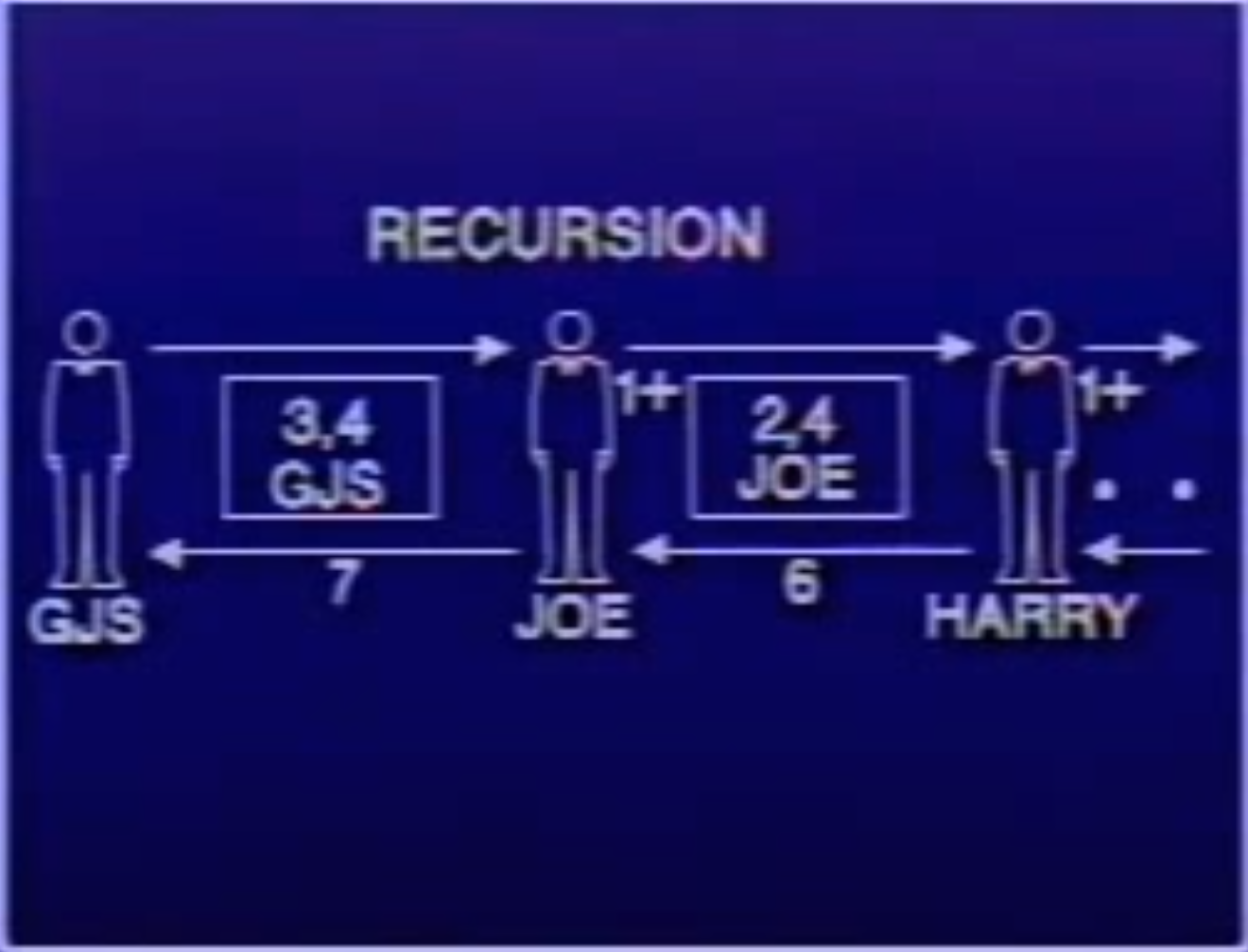

The recursive process:

(define (sum a b)

(if (= a 0)

b

(+ 1 (sum (- a 1) b))))

The same story, now we follow the recursive procedure. First the author GJS writes a note with (3, 4, GJS) and passes it to Joe. Joe will write a new note with (2, 4, Joe) and passes it to Harry, but he cannot go home yet, he has to stay and wait for Harry to tell him an answer, and he has to add 1 to that answer and pass it back to GJS.

Note that now that every person has to write a new note with his name on it. And has to wait for the next person’s answer so that he can add 1 to it and pass it to the previous person.

Now that we understand the two types of recursive procedure. We can go back to answer the question about looping constructs.

We can now easily see that the iterative process is actually equivalent to the looping constructs.

But unfortunately most implementations of common languages (including Ada, Pascal, and C) are designed in such a way that the interpretation of any recursive procedure consumes an amount of memory that grows with the number of procedure calls, even when the process described is, in principle, iterative. The implementation of Scheme does not share this defect. It will execute an iterative process in constant space, even if the iterative process is described by a recursive procedure. An implementation with this property is called tail-recursive. With a tail-recursive implementation, iteration can be expressed using the ordinary procedure call mechanism, so that special iteration constructs are useful only as syntactic sugar.

Now I hope that you have gained a deeper understanding about looping and recursive and the relation between the two.

~THE END~

Share this post

Twitter

Google+

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Email