Punk Rock Languages

A Polemic - by Chris Adamson

It’s rare that in one article the author praises C and JavaScript at the same time. After I read this one, I fear that it may vanish any time soon, so I decided to repost it here.

That C has won the end-user practicality battle is obvious to everyone except developers.

The year is 1978, and the first wave of punk rock is reaching its nihilistic peak with infamous U.K. band the Sex Pistols touring the United States and promptly breaking up by the time they reach the West Coast. Elsewhere, Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie are putting the finishing touches on their book The C Programming Language, which will become the de facto standardization of the language for years. While totally unrelated, these two events share a common bond: the ethos of both punk rock and C have lasted for decades, longer than anyone in 1978 could possibly have imagined.

And in many important ways, C is the programmer’s punk rock: it’s fast, messy, dangerous, and perfectly willing to kick your ass, but it’s also an ideal antidote to the pretensions and vanities that plague so many new programming languages. In an era of virtual machines and managed environments, C is the original Punk Rock Language.

Lightning Strikes (Not Once But Twice)

C has all the power of assembly language combined with all the elegance and poetry of… assembly language.–Erica Sadun

Punk rock emerged as a reaction to the increasingly self-indulgent and misguided musical trends of its time, with progressive rock insisting on merging in influences from jazz and classical music (typified by Emerson, Lake and Palmer performing Mussgorsky’s “Pictures At An Exhibition” as a rock album), and second-rate guitarists noodling away in awe of Hendrix and Clapton with what Joey Ramone called “endless solos that went nowhere.” Punk stripped away the nonsense of the times by focusing on faster, shorter, simpler songs. Preparing America for the Sex Pistols, Time magazine wrote “in the U.S. the movement is more purely musical: groups like the Ramones, Talking Heads, Television and Richard Hell and the Voidoids have rejected the rococo sophistication of much 1970s rock and turned back to basic buzz and blast.”

C’s development was, if anything, the opposite: it was meant as an alternative to programming the PDP-7 in assembly. In Dennis Ritchie’s history of the language, he describes it as the result of several attempts to provide higher-level languages for the platform, a successor to BCPL and B (which Ritchie describes as “BCPL squeezed into 8K bytes of memory and filtered through [Ken] Thompson’s brain”). But this development wasn’t driven by academic niceties or intellectual noodling. It was about getting stuff done. As Ritchie recalls:

“By 1971, our miniature computer center was beginning to have users. We all wanted to create interesting software more easily. Using assembler was dreary enough that B, despite its performance problems, had been supplemented by a small library of useful service routines and was being used for more and more new programs.”

Punk is famous for needing little more than three chords. C basically has three types—int, float, and char—embellished only by being able to increase their bit-length as longs and doubles. It’s gallingly simple to modern eyes, but hones quite closely to what’s actually on the CPU. Look through the x86 or ARM7 instruction set and you’ll find no references to Unicode strings or “objects” of any kind; what you get is simple arithmetic and logical operations that work on operands of 8, 16, and (maybe) 32 bits. C is simple because, at their core, computers are simple.

Of course, you can build any amount of complexity you like atop this simple foundation. The American National Standards Institute (ANSI), spent most of the 80s codifying the C Standard Library, the collection of always-available libraries to perform essential operations like memory management, string manipulation, and networking. And you can then build your own libraries atop these. But as long as you’re still working in C, it’s fairly easy to keep your code running close to the metal, working with simple structures and function calls. Ritchie again:

“Despite some aspects mysterious to the beginner and occasionally even to the adept, C remains a simple and small language, translatable with simple and small compilers. Its types and operations are well-grounded in those provided by real machines, and for people used to how computers work, learning the idioms for generating time- and space-efficient programs is not difficult. At the same time the language is sufficiently abstracted from machine details that program portability can be achieved.”

With the rise of object-oriented programming, new languages co-opted C to provide OO features: C++ has proven the most popular over time, while the Smalltalk-flavored Objective-C might well have remained a footnote had it not been adopted by NeXT, which led to its use in Apple’s popular products. Even so, within these languages, you still mix procedural C calls with the object-oriented additions.

Police On My Back

Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated?–Johnny Rotten, January 14, 1978

Segmentation fault–Command-line output of a C program with a broken pointer.

The largely unmanaged freedoms of C, C++, or Objective-C provide the opportunity to cause extraordinary havoc with your code, intentionally or not. What’s most distinctive about C compared to other popular languages today is the exposure of memory pointers, and the disasters that come with their misuse. But then again, this is an intrinsic part of how computers work: you have a big block of memory (real or virtual), containing the system, your program, and other programs. If you can address any point in memory, and you read or write to an address that your program doesn’t own, what should happen? One option is to allow programs to gallivant through each other’s memory space. As entertainment, this is “Core Wars”; as a coding error, it’s a security nightmare. In the real world, such mistakes are prohibited by operating systems, and the offending program is terminated.

A lot of people find this price of failure too high, even though the fix is to just write better code, and instead opt for an even more draconian option: taking away the keys. Most modern languages provide their own memory management paradigms, and never allow the developer to see a pointer. Take a look at the monthly TIOBE Programming Community Index, and you’ll see three kinds of languages in the top 10:

-

C and its OO derivatives: C, C++, Objective-C

-

Interpreted languages: Python, PHP, Visual Basic, Perl

-

Virtual Machine languages: Java, C#

The latter two groupings add profound new layers to the programming model: interpreters to parse and interpret program code, or virtual machines that create an entirely new execution environment for bytecode. Importantly, in both of these cases, the programmer’s code is not the executable: run ps and you’ll see that the interpreter or VM is what’s running, not your code per se.

As we build abstraction upon abstraction, we get further and further away from what’s really going on in the CPU and memory. In 2011, we now have popular scripting languages like Scala and Groovy whose interpreters run in the Java Virtual Machine. We’ve gone from working with the same data types that the CPU processes to an elaborate stack of layer after layer of artifice and illusion. If C is a punk band, blaring out the two or three basic types that the CPU understands, this new style of programming is Rick Wakeman hiring the London Symphony Orchestra to play backup for his synthesizer.

Now we have an Anti-IF Campaign, which vows we will get more agile code by casting off if statements, replacing them (or at least moving the problem) through the use of elaborate subclassing and other language novelties.

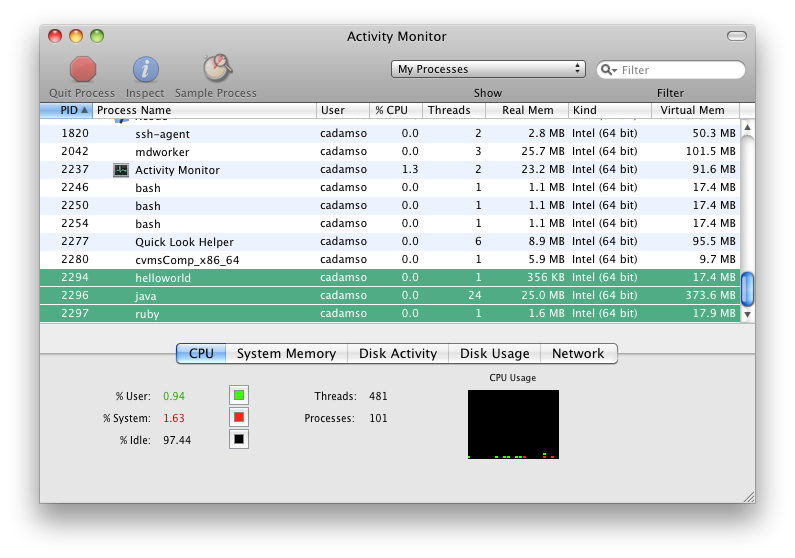

There’s a price to pay for all this, the “abstraction cost” of creating general-purpose interpreters and virtual machines. Consider “Hello World” in C, Ruby, and Java, with an added sleep so the program doesn’t immediately terminate:

#import "stdio.h"

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

printf ("hello, world!\n");

sleep (30);

}puts ’Hello world’

sleep (30)

public class HelloWorld {

public static void main (String[] args) {

System.out.println ("Hello World!");

try {

Thread.sleep (30000);

} catch (InterruptedException ie) {}

}

}Run all three of these and take a look at the resources they demand for this trivial program. As the figure illustrates, on Mac OS X the C program takes 356 KB, the Ruby interpreter 1.6 MB, and the Java Virtual Machine 25 MB. Java also starts up 24 threads for this trivial program.

Nobody Likes You

As someone remarked: There are only two kinds of programming languages: those people always bitch about and those nobody uses.–Bjarne Stroustrup

We are the cries of the class of ’13 / Born in the year of humility / We are the desperate in the decline / Raised by the bastards of 1969—Green Day, “21st Century Breakdown”

Fans defend scripting and VM languages with arguments based around the idea of “programmer productivity”: that faster CPUs and cheaper memory make it more economical to accept these abstraction costs, in the interest of getting working code out the door faster. Java has long been accused of tolerating bad programmers gladly, but that knock against it applies equally well to all the scripting and VM languages.

Furthermore, look who’s making these languages popular: it’s the web developers. All of the scripting and VM languages in the TIOBE top 10 are primarily associated with developing web applications. Yet when we cast our gaze over to the desktop and the mobile device, the scripting and VM languages largely disappear. PHP is clearly meant for web use, but Ruby and Python are general-purpose enough that they could be lashed to a UI framework to power desktop apps. In fact, Apple did just this in Mac OS X 10.5, making Ruby and Python first-class languages for Cocoa development. But in 10.6, the Ruby and Python templates have disappeared from Xcode. It appears that few developers took the bait, just as Cocoa-Java found few takers in earlier versions of Mac OS X and was retired.

(For those still willing to give scripting for OS X a go, Brian Marick’s Programming Cocoa with Ruby is a fine introduction to this, wisely presenting Cocoa to the Ruby developer, instead of Ruby to the Cocoa developer.)

The VM languages have had some success on the desktop, most obviously C# in the Windows realm, where the go-to language was once Visual Basic, whose compiled P-code was also typically run by a VM. But Desktop Java’s long miserable history of underachievement tarnishes the viability of desktop VMs, and with one exception (highlighted later in this article), there’s little apparent real-world use of scripting languages on the desktop. Even on Linux, where scripting languages thrive on the server, GNOME, GIMP, vi, and emacs are written in C, while KDE, Firefox, Thunderbird, VLC, and OpenOffice.org are in C++.

Meanwhile on smartphones, the C languages are the only real option for Apple’s market-leading iOS devices. And while Android uses the not-really-Java-nudge-wink “Dalvik” VM, it offers the Java Native Interface as an escape slide to C for performance-hungry applications like games.

The takeaway is that when your code is running in the immediate presence of the user—on his or her desktop, phone, game console, or tablet—the advantages touted by interpreted and VM languages suddenly diminish. Without network latency to hide behind, and with resources at a premium (particularly on the mobile device), the extravagances of the webapp stack suddenly becomes a lot less desirable. Users see slow, memory-intensive applications on their systems and say, as the last Clash album did, “Cut The Crap.”

That C has won the end-user practicality battle is obvious to everyone except developers. Paul Graham’s essay “The Hundred Year Language” manages to not mention C, despite the fact that it’s already got 40 years under its belt, and has never ranked lower than #2 on the TIOBE list.

Come Out and Play

Well, you know, for me punk has always been about doing things your own way. What it represents for me is an ultimate freedom and sense of individuality. Which basically becomes a metaphor for life and the way you want to live it.–Billie Joe Armstrong

C is quirky, flawed, and an enormous success. While accidents of history surely helped, it evidently satisfied a need for a system implementation language efficient enough to displace assembly language, yet sufficiently abstract and fluent to describe algorithms and interactions in a wide variety of environments.–Dennis Ritchie

One of the defining traits of punk is the do-it-yourself (DIY) ethic, a rejection of the need to buy products or use existing systems, and instead to attend to your own needs. This attitude clearly suits C programming as well. Indeed, it defines the language’s history, with the messy incompatibilities of early versions of the language on different hardware, and the development of wide-ranging libraries that don’t always use like-minded idioms or patterns. As the decades have rolled on, a motley collection of C code has been developed by programmers around the world and across the decades, providing everything from XML parsing to 3D graphics, even if a libxml call looks nothing like an OpenGL one.

Some of these libraries are open-source and part of GNU. Others are commercial and liberally licensed. And there’s an incalculable amount of proprietary C code hidden away in businesses around the world. It doesn’t matter: C has no licensing concerns of any kind. C isn’t owned by a company (like Java, Objective-C, and C# effectively are), but neither is it a slave to the FSF or any other political movement. Any programmer can pick it up and use it for any cause, good or evil, that he or she sees fit. No $99 developer program memberships, no license agreements, no genuflecting to Richard Stallman… just code, compile, and run.

The Kids Aren’t Alright

Punk is musical freedom. It’s saying, doing and playing what you want. In Webster’s terms, ‘nirvana’ means freedom from pain, suffering and the external world, and that’s pretty close to my definition of Punk Rock.–Kurt Cobain

Having made the case for C as a sort of “punk rock language,” it’s worth asking what other languages share C’s traits of ruthless usefulness. Let’s continue the musical analogy: once the original wave of punk spent itself, its values were adopted by a number of successor genres, like post-punk, power pop, and new wave. Bands like The Clash and Television combined punk’s immediacy with better chops and more outside influences. The Offspring and Green Day revived punk in the 90s with catchy melodies, launching an era of pop punk that persists to this day. In the early 90s, punk contributed to grunge, which helped end the era of glammy hair metal (sorry, Jon Bon Jovi and David Lee Roth). As long as there’s a musical trend that’s too full of itself, punk or one of its spin-offs will be waiting to tear it down.

What’s the least pretentious language in widespread use today? Surely it has to be the much-derided JavaScript. Though it’s one of many languages that inherits much of its syntax from C, it is an interpreted language, object-oriented and packed with novel features like dynamic typing, first-class functions, and closures.

It is possible to write elegant, clever code with JavaScript. In true punk rock fashion, almost nobody does.

JavaScript in anger is a brutally efficient language. Used primarily in the context of a browser, it is often used to slash out quick-and-dirty onClick() implementations. Despite being burdened with the confusing “Java” name, no class declarations, package and visibility statements, or other niceties are required; often enough, JavaScript code is rammed into the attribute of an HTML element.

Older developers bemoan the lost days when computers shipped with BASIC built in, or of learning scripting with HyperCard. “Where,” they ask, “are today’s kids learning how to program?” missing the browser that’s staring them in the face. The web browser offers a JavaScript interpreter and enough toys in the DOM to keep the young programmer occupied for years. Anything that could be written in AppleSoft BASIC can just as easily be created with JavaScript and the <canvas> tag, and the presence of the tree-structured DOM and JavaScript’s support for regular expressions give the young programmer access to more significant and interesting data structures than us old folks were ever going to develop on a middle school VIC-20. And thanks to the arms race between browser developers, JavaScript performance continues to improve by leaps and bounds.

Shouldn’t beginning programmers learn from a more cleanly structured language? That’s always been the complaint, but the slop of BASIC didn’t harm my generation of developers (and mandatory Pascal didn’t clean us up), so why should we fear that JavaScript will pollute the next generation? If anything, JavaScript’s freedom to be as messy and unstructured as you want is a gift: once the mess gets out of hand, the young developers will have to figure out how to bring in classes, structure, OO, and the other tools that JavaScript provides to set things right. But it’s DIY: JavaScript lets you be a good programmer, but doesn’t force you to. How you structure your code and how you deal with problems is up to you.

Institutionalized

Don’t do anything by half. If you love someone, love them with all your soul. When you go to work, work your ass off. When you hate someone, hate them until it hurts.–Henry Rollins

I’ve probably written an ungodly amount of C code, but I hate C with a passion. I’ve been writing a lot of Objective-C code lately… which just fuels my hatred for C. .h files are absolutely the work of the devil.–James Gosling

Not every language can be “punk.” Not every language should—sometimes you do want the protections and comforts of the Web scripting languages, just as sometimes you’d rather listen to The Beatles than Black Flag. So, can we decide where to draw the line? Since C and JavaScript seem to have become punk rock languages through their evolution and use, not from their design, it might be more useful to list the traits that we associate with punk rock languages.

Here are some signs that you’re working with a punk rock language:

-

Owned by nobody—As pointed out before, C isn’t owned by any company, nor is it controlled by the FSF or any other part of the free software movement (though it was clearly instrumental in the development of Unix, Linux, and the GNU software stack). Similarly, JavaScript is nobody’s property. It’s OK for these languages to have formal specifications, and to accept contributions from all sources, but no one body controls them, and that’s a great thing.

-

Allows the user to apply as much or as little structure as he or she chooses—It’s not punk to keep the training wheels on all the time.

-

Is used in real-world systems or applications—Perhaps we can create a category of “garage band languages” for those that aren’t ready to play real gigs yet. But until it’s useful to someone, a language with no users is always at risk of turning out to be a poseur.

-

The natural appeal of the language is to write software with it, not to mess with the language itself—Solve your users’ problems rather than indulging your own programming fetishes.

-

Inspires disdain, disgust, or outright hatred from people smart enough to know—Any idiot with a Slashdot handle can talk crap about anything. It’s when you piss off the smart developers that you know you’re working with something interesting.

Feel free to come up with your own definitions and categorizations. After all, if there are too many rules, it’s not punk anymore.

Good Riddance (Time of Your Life)

So, you have a choice. You can keep adopting the flavor-of-the-month language, each one giving you some beautiful new way to iterate over collections, so your method to collate all the user’s previous transactions into a table can be done in 10 lines of code instead of 15. Or maybe you can use so much duck-typing that you get to add the string “4” to the number 2 (and be able to accurately predict whether you’ll get the string “42” or the number 6). Or maybe the next language will do away with all the traditional branch and loop statements (if, for, while, etc.), in favor of some new exotic side-effect-driven style of programming that will be awesome as soon as you and everyone else “get it.”

Or, maybe you can drop the pretensions, dismiss the illusions, and tear down the fake world of intents, monads, and whatever crazy new thing they come up with next.

What will be left is you, your code, and a CPU waiting to do stuff.

Kick… ass.

Chris Adamson is a writer, editor, developer, and consultant specializing in media software development. He is the co-author, with Bill Dudney, of iPhone SDK Development. He has served as Editor for the developer websites ONJava and java.net. He maintains a corporate identity as Subsequently & Furthermore, Inc. and writes the Time code; blog. He listened to The Clash, The Offspring, Green Day, and Fear while writing this article.

Twitter

Google+

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Email